WS103

Lessons for Preparedness: Is There a Recipe for Success?

Contact Person : Padmaja Shetty, pshetty@usaid.gov

08

Dec

The global health community has been actively preparing for large-scale epidemics and pandemics for many years, often saying it was a “matter of when, not if.” The SARS epidemic, 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and West Africa Ebola epidemic have served as reminders of this threat, resulting in global action and commitment to cooperation through high-level meetings and resolutions, including the 2018 Prince Mahidol Conference’s “A Call to Action on Making the World Safe from the Threats of Emerging Diseases.” The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that even with these preparedness efforts and investments, national responses can vary widely. Some countries were better able to leverage their previous preparedness efforts and investments and managed to rapidly implement successful public health response interventions and adapt existing systems. The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board has found that preparedness and subsequent resilience of societies can be broken down to five necessary and interconnected components, including responsible leadership, engaged citizens, agile systems, sustained financing and robust governance. The ongoing response to COVID-19 has provided a wealth of information and insight on how preparedness can be improved, recognizing that there will continue to be future threats of this nature.

Along the human dimension, preparedness requires both 1) responsive leadership that is based on transparent use of evolving evidence, a multisectoral, whole of society approach and a commitment to equity and social protection, and also 2) an engaged civil society that protect the vulnerable and keep leadership accountable. In addition, dependable and sustained financing (domestic and international) at the scale required for prevention and preparedness is critical to ensure the systems, human resources and commodities are planned and accessible when needed. Finally, preparedness requires having agile systems that can address the emergence of pathogens with pandemic potential; support open and transparent sharing of information on outbreaks and similar events; facilitate R&D and access to medical countermeasures; provide surge capacity for clinical and other essential supportive services; and provide social protection and safeguard the vulnerable.

The right metrics can help a country to track their progress and the gaps in its national preparedness systems and guide domestic and external investments. However, existing preparedness indices have failed to provide an accurate picture of national preparedness and to predict countries’ response capabilities and resilience to global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

This webinar will examine the lessons learned from COVID-19 to date with regards to preparedness and how these lessons can be applied by practitioners, policy makers, and community leaders.

This session will explore the following topics:

- How can leadership and governance structures for preparedness be transformed to facilitate early decisive action by leaders, ensure the transparent use of evidence, and promote a multisectoral, whole of society approach to health emergency preparedness and response?

- How can leadership be responsive to communities and promote trust and equity?

- How can financing for preparedness be reformed so that it is sustainable, responsive, reliable and is available on the scale necessary to ensure that the critical components of preparedness are in place, both at the national and global level?

- What measures can be taken to ensure systems are more agile and to promote better coordination at the national, regional and global levels so that we improve early alert and information sharing; facilitate research and development, manufacturing, deployment and allocation of countermeasures; and strengthen supply chains?

- How can we adequately measure progress on these dimensions of preparedness?

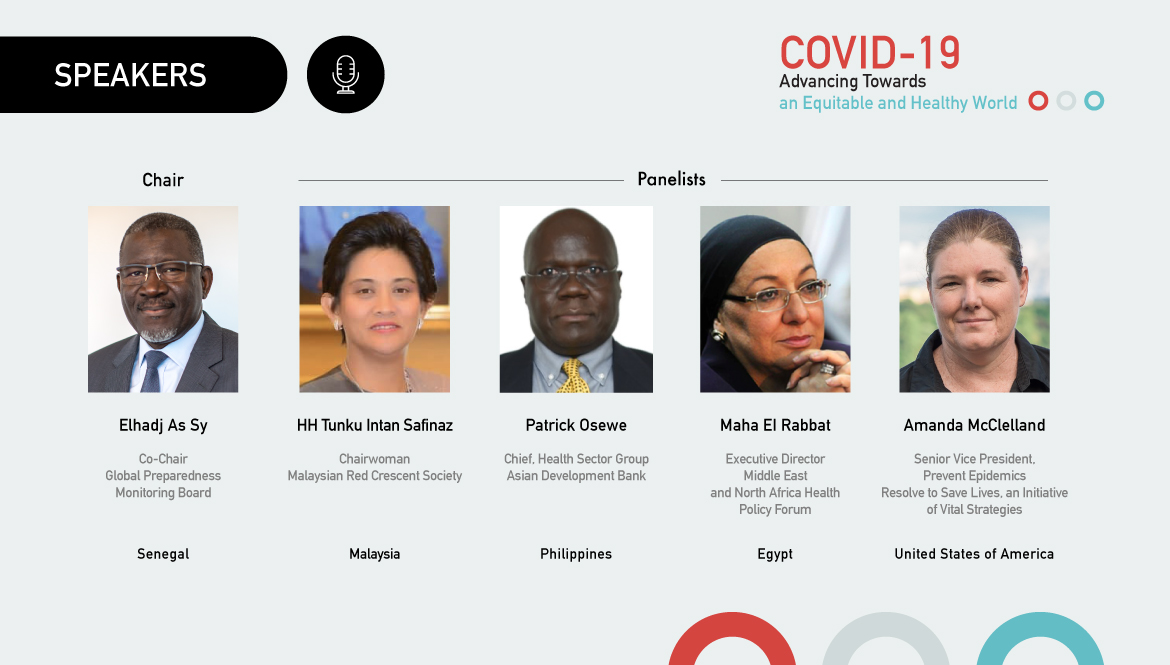

PANELISTS

Biosketch

Amanda McClelland

Elhadj As Sy

HH Tunku Intan Safinaz

Maha El Rabbat

Patrick Osewe